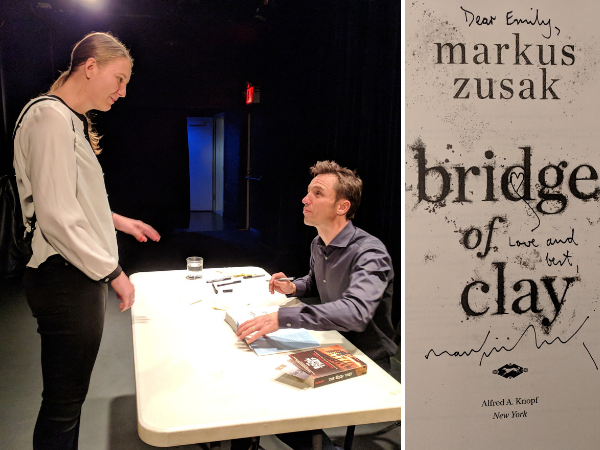

Markus said he got the idea for a story about a boy named Clayton building a bridge when he was 20 years old, before he even published his first novel, The Underdog. After he wrote a version of the book way back then, he stepped back and thought, “This isn’t it.” After publishing The Book Thief in 2005 (2006 in the U.S.), Markus revisited the idea, and Clay’s story underwent 13 years of being reshaped and reformed. “Clay can be molded into anything,” Markus said, “but it needs fire to set it.” As years passed, Markus got caught up in trying to do right by his reader; eventually he shifted his focus to trying to do right by the Dunbars. He made major changes draft to draft; the number of brothers fluctuated from five to two and back to five, and the narrator changed from being the neighbor girl Maggie to the middle brother Henry and even to the boys’ mother from beyond the grave before Markus settled on the eldest brother, Matthew. After working simultaneously with editors in the U.S., UK, and his native Australia, Markus was finally able to announce back in March that Bridge of Clay was done.

Was he relieved, delighted to finally be finished? He admitted it was a bit of a downer at first, but what did he expect when he’d lived and wrestled with these characters for as long as he had? He appeared both relieved and delighted as he spoke that evening, though, presenting the book like a gift to an audience of dedicated readers. I wanted to share some of highlights of the event, pithy quotes and stories I scrawled on my program in the darkened auditorium of Manhattan’s Symphony Space. (I loved your words, Markus, and “I hope I have made them right” in my memory, but please forgive any slight paraphrasing.) “I feel like a tradesman most of the time,” he said of the arduous process of writing Bridge of Clay. He discussed a motif from the book: when you go to see Michelangelo’s David in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, you must first walk down a hallway lined with the Slaves, unfinished statues still trapped in stone, struggling to get out. Markus said he wants to be the David, but most of the time he feels like the Slaves. As the artist, he aims to free his characters from the stone, chipping away at the excess to get at the core of who they are.

Markus’s family attended the reading, sitting a few seats to my right, and he described their role in bringing him back to earth throughout the writing process. When his daughter was 3, she wandered into his writing room and requested that he read her his book; he started from the beginning of Bridge of Clay, but she interrupted him mid-sentence to say: “I don’t think I like that very much.” “Well, it’s not really for your age group,” he tried to counter, but she had already toddled out of the room. As his children grew, Markus kept writing, but no book came out. One day, when he told his daughter he had to go do some work, she remarked, “You, working?” Admittedly, Markus said with a laugh, his daughter was 3 months old last time he put out a book. He joked that if you did the math for the final length of the book and how long he spent writing it, he averaged about 1.9 words a day. There were times he thought he wouldn’t finish, and he had conversations where he expressed fear that he might be washed up. At one point in the grueling process, his wife gave him one week to “get right with Clay.” The week passed with no improvement, and she told him he should take a step back and work on something else—his blog. Begrudgingly, he did, but he found himself thinking: “Before, when I was writing the book, I was writing it for the world championship of myself, and now I’m doing this.” Six weeks later, he was back at work on Bridge of Clay. When the writing was good, snippets of his life worked their way into the narrative. Once, while he was working shirtless in the garage, his son wandered in and asked, “Dad, what are you doing here in just your nipples?” This line is said by the youngest Dunbar boy in the book. As Markus reworked Bridge of Clay over and again, he began asking his editors and beta readers to answer one question about it: “Alive or dead?” Did the writing have a heartbeat? Was there something there? Writing what is now the prologue brought the project back to life for him, and he began enjoying the process again. He originally wrote the scene from Henry’s perspective, however, not Matthew’s. This created a lot of narrative issues, however; in the end, Markus changed the narrator to Matthew largely because doing so created fewer problems.

A post shared by Markus Zusak (@markuszusak) on Oct 22, 2015 at 2:18pm PDT When people compliment his imagination, Markus says, “I actually don’t have a great imagination. I just have a lot of problems.” Imagination comes into play when working around those problems. “Not very much comes naturally to me,” he added. He’s always had to struggle at everything, his books included. He described writing the first 250 pages of The Book Thief during a blissful January month of Australian summer, only to read it back and think, “Well, that’s pretty ordinary—ordinary being a euphemism for terrible.” Writing is an ongoing process for Markus. He’ll take a stab at something, look at it and say, “No, that’s not the book,” and start again. He says he always tries to write books that are a step beyond what he thinks he’s capable of. As the poet Robert Browning once said, “Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, / Or what’s a heaven for?” “Where do you get your ideas?” someone asked. “Most ideas are accidental,” he answered. “How do you know when an idea’s worth pursuing?” an aspiring writer wanted to know. “When your ideas start moving left or right of where you’ve started, that’s when you’re close.” The book’s structure made such a shift several times. Back when the narrator was still the neighbor girl Maggie, Markus wanted to divide the book into 500 chapters, each a piece in a sort of literary jigsaw because Maggie loved puzzles. The people he told this to were less than thrilled with the concept, and it never ended up working on the page, so he took it in a different direction. Now the book is divided into eight parts, the name of each section adding on to the previous: part one is “cities,” part two “cities + waters,” part three “cities + waters + criminals,” etc. He wanted readers to think, “Here is a story being built like a bridge.” The last addition to this sum is “fire,” the thing which sets Clay into a final form. “We’re carrying our stories with us,” Markus said, “and that’s what we’re made of.”

A post shared by Markus Zusak (@markuszusak) on Mar 13, 2018 at 1:29pm PDT An aspiring editor, I asked Markus to talk about his relationship with his various editors. How did he balance getting feedback from all three? He said this was his first time working with all three at once, as this was his first book to publish simultaneously in multiple countries. (It was also his first time using Track Changes, and he said he liked the collegiality it brought to the process.) It was a lot to balance between the three, he said, but each editor is completely different. His U.S. publisher acts as the calming voice, whereas his UK publisher is a little more fiery in her comments. As for his Australian publisher, Markus said she is both a passionate reader and a dear friend. “That’s what I wish for you in your career,” he said—that I would build a relationship with my authors, a friendship so close they’re almost family.

But of course, all good families fight. Once, after Markus emailed his Australian publisher to say he wasn’t going to be able to deliver, she told him she didn’t respond for a full day cause at the time all she wanted to do was punch him in the face. “Never say that to an author,” he told me. “Not unless you know them super well.” “Write that down,” the lady sitting next to me said. So I did. MJ asked one final question: How does Markus want readers to feel when they’ve finished the book? “I want them to feel like they got run over by a truck,” he said. “And I hope by the end of it, you feel like a Dunbar boy.”