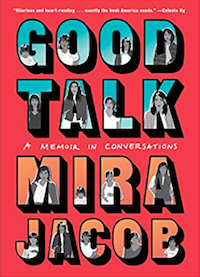

When I was teaching in NYC public schools, I used to commute on the always crowded crosstown bus. One afternoon, I looked up from the high school essays I was reading and noticed a caregiver and a child reading a book aloud together. I heard them notice details on each page and laugh at the characters’ antics. How special, I thought. Such a private moment on display for all these tired commuters to hear or tune out. I felt honored to witness it. Now I’m a parent having these talks at home with my own child, often wondering what territory we’re about to enter and how to keep the conversation flowing as long as possible. I can’t help but wonder how these talks go in other families. But I’m no longer a crosstown bus commuter, and I don’t get many opportunities to eavesdrop on the good talks children have with their trusted adults. Reading Mira Jacob’s graphic memoir Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations put me back on that crosstown bus. And the first few pages relayed a conversation that put me on the edge of my seat. Jacob invites us to witness an impromptu discussion she and her son have about race, equity, and identity. Her son, wanting to know more about his idol Michael Jackson, asks increasingly complicated questions like “Was Michael Jackson brown or was he white?” which leads to “Is it bad to be brown?” Jacob’s responses alternate between objective honesty and overcompensating enthusiasm. When her son ultimately asks, “Are white people afraid of brown people?” she quietly considers, “Sometimes.” When he chillingly wonders, “Is Daddy afraid of us?” she emphatically states, “NO.” Jacob confesses to a friend that she’s overwhelmed by her son’s questions in the moment. Do I have to “make up all the rules” for a good talk? she wonders. Where’s the balance between treating his questions with respect and telling him too much? She even turns on herself as a parent, worried she’s “fucking him up” with her responses. For Jacob, her son’s questions about identity and belonging are difficult to respond to not just because they are tough questions, but because she discovers how confused she actually is about the answers. The rest of the memoir intersects formative experiences from her past with current conversations with her son—the same conversation dance that I find myself doing during talks with my child. I’m also an Indian American woman married to a white American man and we have a mixed race child about the same age as Jacob’s son. And like him, my child has been commenting on race, difference, and identity since the toddler years. Each comment catches me unprepared, each question has me stumbling and wondering and rephrasing. To see Jacob equally flummoxed when faced with those same sensitive topics allowed for a kinship I really needed. When my daughter was a toddler, we moved from a racially diverse city to one that was a lot more white. While we drove home from preschool one day, she stated matter-of-factly, “All my friends at school are white.” I heard this statement as more than an observation. It felt like critique, complaint, and wonder all in one. It was a sensitive topic for me, having had the same experience from pre-K through college. A thought that was probably already simmering came to a boil, Why did we move here? Was she identifying a problem and wanting a solution? My urge was to fix it. Like Jacob, I didn’t know the rules for responding. I looked in my rear view mirror and simply affirmed what she had so astutely noticed. “Yeah, that’s true. That was true for me sometimes, too, when I was a kid.” Our talk continued from there, each of us sharing observations and anecdotes, eventually asking and answering each other’s questions. Throughout my child’s toddler years, I felt an urge to dive deep into the complex issues connected to her simply stated observations. “White kids color in drawings of people with peach crayon but brown kids use brown.” “All the kids at that school are black.” “My friends think I have a tan.” “I never see half-white, half-Indian girls in books.” “I noticed that most athletes on TV are black.” I heard each new observation as a question or a problem she wanted solved. My initial instinct was to answer the best I could in the moment, provide background knowledge, and maybe even solutions. Should I explain things like “cultural appropriation” and the difference between racism and bigotry using simple language and child-friendly metaphors? I decided to acknowledge her comments as the casual observations they were. I would listen, maybe relate, and possibly ask a follow up question. The deeper engagement with the issue would develop over time, through talks with others, reading stories together, and chatting about our days. Literature of all forms allows us to eavesdrop on conversations between characters of all backgrounds and experiences. In fact, Salman Rushdie once defined literature as “the one place where we can hear voices talking about everything in every possible way.” Jacob’s Good Talk relays conversations I think we all could benefit from hearing. When we’re struggling to navigate murky conversational waters with our kids, swaying from objective facts in simple terms to flat out lies about safety and equity in a falsetto tone, it’s reassuring to know we’re not alone in our uncertainty. And as Jacob ultimately reminds herself, and tells her future son, it’s the questions our kids are asking that are actually the answers to our own worries. If a kid “grows up to be the type of person who asks questions about who [they] are, why things are the way they are, and what we could do to make them better,” then we “still have hope for this world.” Our young children’s questions are challenging when we first hear them because we assume we need to have answers. But wondering and questioning together might be better than any answers we could offer.